How to Delegate More Effectively: Four Approaches

Trust between people is not enough to make delegation work. Leaders must also scrutinize the level of trust in the process — and match their approach carefully.

News

- Identity-based Attacks Account for 60% of Leading Cyber Threats, Report Finds

- CERN and Pure Storage Partner to Power Data Innovation in High-Energy Physics

- CyberArk Launches New Machine Identity Security Platform to Protect Cloud Workloads

- Why Cloud Security Is Breaking — And How Leaders Can Fix It

- IBM z17 Mainframe to Power AI Adoption at Scale

- Global GenAI Spending to Hit $644 Billion by 2025, Gartner Projects

Carolyn Geason-Beissel/MIT SMR | Getty Images

Delegation still bedevils many leaders. From the overworked manager trying to alleviate burnout to the vice president trying to take a vacation, many leaders need to delegate more but avoid it. Transferring responsibilities to someone else often creates worry, friction, or unsatisfying results. But delegation is not optional: Individuals and organizations can’t grow unless people learn how to effectively delegate both tasks and decision-making.

In our work over the past decade, we’ve seen delegation arise as a leadership challenge in organizations across many industries. Indeed, in health care, manufacturing, and life sciences companies alike, the question of when and how to delegate remains difficult. To address this problem, we developed a framework based on two core dynamics at the heart of effective delegation: people and process. Trust in people is nothing new to conversations on effective delegation; however, trust in organizational processes is an equally important but underappreciated consideration in delegation decisions.

In our work with leaders, we’ve seen that no matter how reliable an individual employee may be, if the underlying organizational process that is central to the delegation is erratic or underdeveloped, delegation tends to break down. So our framework advises leaders to consider two key questions when entertaining the delegation scenarios: “To what extent do I trust the people?” and “To what extent do I trust the process?”

Trust in people is based on a repeated track record of meeting goals, shared behavioral norms, and consistent interpersonal relationships. It is a trust in the individual’s abilities and skills across a variety of domains: Does Mary have the requisite skills to deliver the results she promised? Does David treat team members in a respectful manner? Trust in process, on the other hand, is based on organizational functioning and speaks to whether a process delivers consistent, predictable, and actionable outcomes: Does the R&D process yield new, marketable products on a consistent basis? Is our sales forecasting process accurate in its revenue predictions?

In our consulting engagements, we’ve seen many well-intentioned and trustworthy individuals fail to execute on a delegated task because of an underdeveloped process; therefore, we suggest that it is the nexus of trust in people and trust in process that should drive the form of delegation that a leader chooses. This article offers a framework with four ways leaders can approach delegation with the confidence that their choice matches the trust level at hand.

Weighing Trust in People and Process

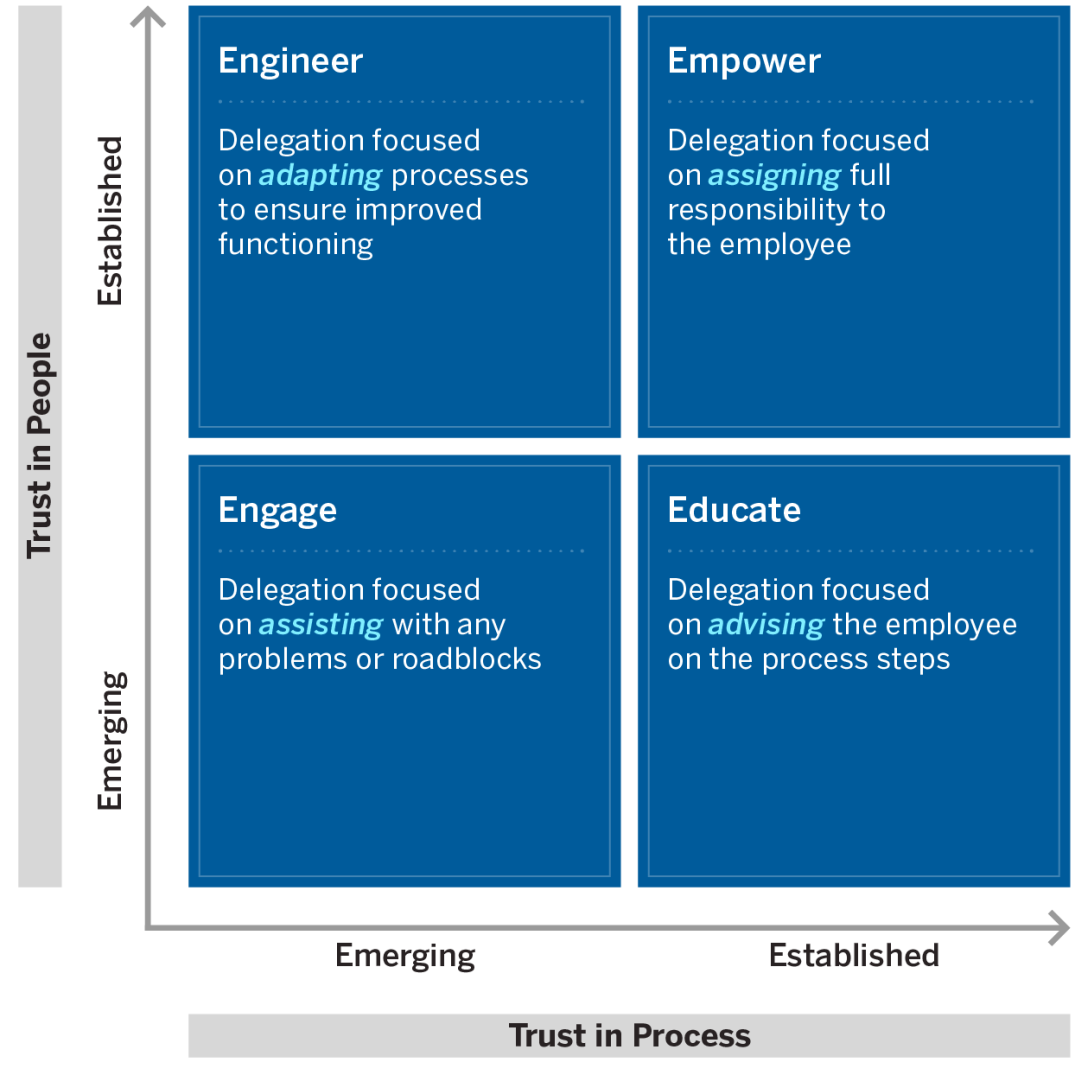

As shown in the grahpic below, we’ve identified four ways to approach delegation based on whether there is emerging or established trust in people and the organizational process: Empower, Engage, Educate, and Engineer.

A Framework for Making Delegation Decisions

This framework helps leaders select the most effective approach for delegating tasks and decisions, given the current level of trust in the people and the organizational process. For example, if trust in both the people and the process is still emerging, the Engage style makes sense: The leader delegates while assisting closely with challenges. Conversely, if trust in the process is still emerging but trust between people is more established, the Engineer style fits: The leader and person to whom the tasks are being delegated both focus on adapting the process to improve it.

1. Engage: Emerging Trust in Both Process and People

We start with a scenario in which trust in both the people and the process is only beginning and not yet established. Here, delegation can break down quite easily if not managed appropriately. Let’s look at an example.

We saw such a dynamic unfold on a newly formed senior management team at a regional hospital. The new CEO had pulled together an interdisciplinary team of veteran leaders with deep knowledge in their respective fields: a chief medical officer, a chief nurse officer, the CFO, and the chief operating officer. While accomplished leaders in their own domains, this team had never worked together before under the leadership of this new CEO. Emerging trust in each other was a significant impediment to delegation. Trust in organizational processes was also quite low, given that the new team had been established to improve the hospital’s quality, safety, and efficacy ratings. In other words, improving processes was at the heart of their requisite work together. Although the CEO tried to delegate decision-making, she struggled with understanding when to step away and let her team make decisions and when to stay closer to the work. The team of seasoned leaders felt as though the CEO was continually looking over their shoulders, often second-guessing their approach. The CEO (rightfully so) worried that important organizational systems and processes were breaking down.

This is undoubtedly a tough situation in which to delegate effectively — and yet not an uncommon one, particularly when a new leadership team is formed, a new leader is brought into an existing team, or organizational processes are tentative or newly established. Across these situations, everyone involved in coordination activities is unsure of the underlying processes and people’s abilities. While delegation can be tough in such a context, it’s not impossible: It requires a degree of engagement from the leader in order to effectively manage delegation.

What does this look like? It involves striking the right balance between allowing the employee to learn and try while remaining close enough to assist and buffer any problem areas or roadblocks. Though it may be tempting to let the team “run with it” on its own, an engaged approach allows for collaboration on decisions. This not only enables the leader to better understand the employees’ capabilities but also lets the team work together to create new processes and fix prior flaws. Is the closely engaged approach permanent? Absolutely not. However, it helps each side to build trust through working together and to better understand the efficacy of new processes.

In the hospital setting, we helped the team to create joint processes from the ground up and then watch each other tackle those processes. This set the stage for both the leader and her team to build trust in processes and people.

2. Educate: Established Trust in Process, Emerging Trust in People

The second approach to delegation is called for when there is a high level of trust in the process but only emerging trust in people. This may be the situation that comes to mind most often when leaders think about challenging delegation scenarios. For example, think about when individuals are promoted into new roles within the organization or when a new hire is brought in from outside the organization and must learn processes that are new to them.

We recently worked with the CEO of a rapidly growing chemical manufacturing company who was looking to develop the next generation of leaders within the organization. To the CEO’s credit, he recognized that while the organization had a track record of success, further growth and strong performance would be possible only if emerging leaders could effectively execute upon delegated work. The organizational processes were well established and had been vetted, but the managers were new. Under such circumstances, it’s like handing a beginning driver the keys to a finely tuned car.

In this scenario, delegation can take the form of educating. Unlike the engagement scenario above, the goal here is for the employee to learn the established process and build confidence in their own ability to carry it through. Over time, this will boost the leader’s trust in the employee’s ability to do so. Delegation through educating means that the leader stays close enough to advise (not assist) the employee through the process steps and answer any questions along the way. This helps the leader build trust that the employee will ultimately do well with decisions on their own.

In the chemical company, as the new managers demonstrated an ability to work within the established processes with positive outcomes, upper managers could reduce their hand-holding and slowly build comfort in entrusting the new managers with additional responsibilities.

3. Engineer: Established Trust in People, Emerging Trust in Process

The next delegation scenario arises when there is established trust in people but only emerging trust in the process. This situation is common in startup companies or during a turnaround when new or reengineered processes are being put into play within established teams. It’s also common in larger companies with an innovation culture grounded in process improvement.

We witnessed this scenario when we worked with a startup medical device company founder who hit roadblocks in effectively delegating to his sales executive. While there was well-established trust between the founder and sales lead (after all, they had built the company together), little to no sales forecasting infrastructure existed in the organization at that point. So when the founder expected the sales lead to execute effectively on sales forecasting, the sales lead felt as though the founder was setting him up for failure by questioning every decision and approach. Stepping back, the dynamic was not surprising: While the founder trusted the sales executive’s abilities, they both lacked trust in an underestablished organizational process — sales forecasting. Pointing this out helped them both understand why there was friction in the relationship. It wasn’t a lack of trust in the sales executive’s skills, and it wasn’t a founder trying to micromanage. The problem was the little-trusted process.

In such instances, the focus needs to be on engineering rather than on delegation through engagement or education so that trusted employees can succeed with an underestablished process. The goal here is for the leader to support the employee in adapting the process to ensure improved functioning. This may mean that the leader becomes a sounding board for the employee’s proposed approaches, or it may require the leader to roll up their sleeves and learn about the process flaws from the ground up. Alternatively, the leader may need to step in to make a final decision and communicate the new process implementation to ensure that the wider culture adopts it.

Here, we start to really see the unique distinctions between the different forms of delegation. A focus on engineering around an underdeveloped process is quite distinct from educating a newer manager on an established process. When there is trust in the individual but a lack of trust in a new or flawed process, open communication and clearly defined process milestones become critical to effective delegation.

At the medical device startup, the founder and sales lead ultimately worked together to engineer and adopt an effective sales forecasting process. As the process began to yield results, a higher level of trust in the process began to develop. With time, the sales executive felt empowered to successfully manage related decisions and outputs.

4. Empower: Established Trust in Process, Established Trust in People

Let’s end with the scenario that offers the most ideal conditions for effective delegation — when trust in people and trust in the process are both well established. This is a prototypical scenario that likely comes to mind when we think of delegation: A leader has a longtime direct report who’s relied upon to “hold down the fort” when the leader is out of town.

Here, delegation is best handled through empowerment. Full responsibility is assigned to a person who has the skills to manage a process that the leader trusts to be effective. The individual is empowered to make any decisions and adjustments as necessary, without concern that the leader will second-guess or backtrack on the approach. This reflects an ideal hands-off approach to delegation that many leaders may envision.

But delegation through empowerment doesn’t happen overnight; it often requires an established working relationship, where the leader and employee have a history of successes together and understand each other’s expectations and work styles. Additionally, both parties not only trust the organizational process but also understand where it sometimes breaks down. Perhaps the leader and delegate have worked together to adapt the process over time, having navigated prior delegation situations in the Engineering quadrant. The leader trusts the employee’s skills and knows that they’ve built a consistently functioning process.

This reminds us of a situation in the chemical company that involved a newly hired vice president tasked with solidifying processes and teams for a growing business unit. After a year in their role, they were successfully handling strategic matters — having empowered team members to manage the day-to-day processes they had engineered together to support business growth. In effect, empowerment allows for just that: Leaders can focus on higher-level strategy when they’ve successfully put in the work to establish trust in people and processes.

However, this delegation approach requires that two critical aspects of the larger culture be nurtured: accountability and voice. When a decision fails, the employee needs to feel comfortable taking accountability for the issues and voicing this to the leader. Accountability should not be the basis of finger-pointing but rather an opportunity for collective reflection. For example, the leader empowers the middle manager to run the business unit in a relatively hands-off manner, but when it’s clear that the unit will miss its forecast for the quarter, the manager takes accountability for the miss and works with the leader to reflect on what went wrong. Empowerment without accountability risks damaging both the relationship and the ongoing effectiveness of the delegation scenario.

As we’ve illustrated, successful delegation requires careful consideration by leaders. This is not like developing a communication style and sticking with it. A leader’s choice of delegation style will vary, depending on the trust level in the person and process at hand. Delegation is not simply about letting people make the decision: The most capable people will fail if the processes are flawed, and even the best processes can be undermined by a poorly prepared individual who has been set up to fail.

Conversations around trust in the process or a person’s abilities may be difficult for leaders to initiate, but doing so is critical to ensuring that delegation leads to individual and organizational success.