Moving Beyond Islands of Experimentation to AI Everywhere

The agile teams needed to kick-start artificial intelligence must give way to companywide structures in order to scale the technology across a business.

Topics

News

- More than 80% of Saudi CEOs adopted an AI-first approach in 2024, study finds

- UiPath Test Cloud Brings AI-Driven Automation to Software Testing

- Oracle Launches AI Agent Studio for Customizable Enterprise Automation

- VAST Data and NVIDIA Launch Secure, Scalable AI Stack for Enterprises

- How Machine Identity Risks Are Escalating in AI-Powered Enterprises

- How Agentic AI Is Reshaping Healthcare

Leo Espinosa/theispot.com

Companies in a wide range of sectors are making significant investments in AI — and are increasingly concerned with how to scale use of the technology to gain benefits from it across their organizations. Too many companies stall out on their AI journey and have difficulty getting past pilot projects or point solutions. That’s not necessarily because the technology is so complex. Our research finds that companies fail to extract the potential business value from AI not for lack of technical expertise but rather due to structural and process issues.

We took an in-depth look at the AI scaling journey of 10 market-leading legacy companies with three to eight years of AI implementation experience across diverse industries, including consumer packaged goods, pharmaceuticals, banking, insurance, security services, and automotive. These companies were at different stages of progress, ranging from relatively nascent capabilities to extremely sophisticated. How they organized their efforts at each stage had implications for what they were able to accomplish. We found that AI projects in enterprises generally begin as what we call islands of experimentation (IOE) before coming together around a corporate center of excellence (COE). Only a small number then move to a sophisticated federation of expertise (FOE) model built on a centralized base of knowledge, systems, processes, and tools, and on decentralized embedded capabilities.

This implies that enterprises with AI ambitions may need to make two potential leaps. Below, we explain why each leap is necessary and discuss how companies can facilitate them.

The Limits of Experimentation

AI initiatives often begin with small, specialized teams exploring specific problems, but these decentralized IOEs make a limited impact. For example, a global pharmaceutical company in our study developed a machine learning tool to predict the next best action for its sales force. Although this tool was successfully launched in one country, it did not spread further because of the company’s highly decentralized structure. Attempts to launch the tool in another country where it would have benefited the company’s operations failed. Eventually, the company realized that the tool was not used widely enough to generate sufficient ROI on the project, and the initiative was killed.

IOEs typically fail to scale as a result of the following four limitations:

- IOEs are usually trained on curated niche data to solve a specific problem, which by its very nature hinders broad usage.

- The limited number and availability of curated data sets means they are eventually depleted (a supporting data architecture for new data sets is typically absent in the initial phase), and projects grind to a halt, even in narrow settings.

- These AI projects are neither visible nor accessible across the enterprise, resulting in duplication of effort, inefficiencies, and higher costs.

- Resource constraints restrict progress over time. Consequently, once the “low-hanging” problems are solved, these islands tend to stagnate or sometimes disappear altogether.

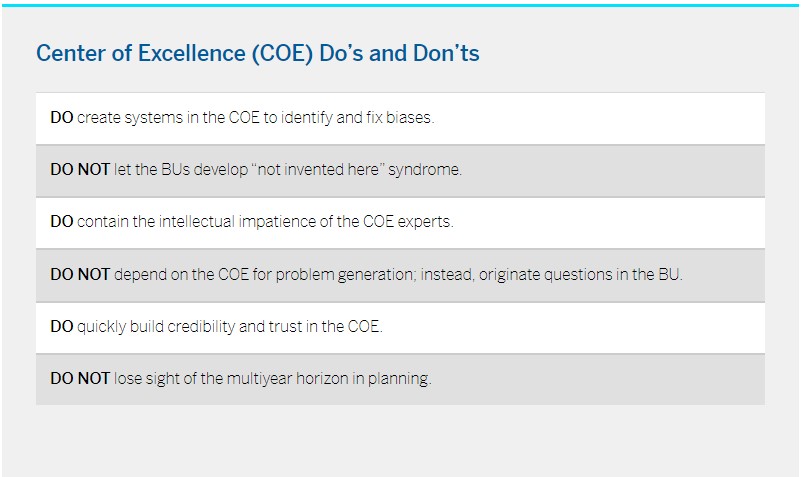

Scaling up from disparate IOEs to build a strong COE is essential in order to create enterprisewide value. IOEs typically focus on tactical initiatives that may generate quick wins but are not necessarily aligned with the company’s strategic objectives. The COE enables a fundamental shift in the type of AI deliverables: They become strategic for achieving key business objectives.

AI initiatives often begin with small, specialized teams exploring specific problems, but these decentralized efforts make a limited impact.

Making the leap from IOE to COE allowed Rímac, the largest insurance company in Peru, to scale up its ad hoc AI experiments aimed at managing churn and understanding customers’ propensity to buy existing products (life, health, and vehicle insurance). The COE was established in 2019 along with a new role, chief AI and data officer, that reports directly to the CEO and sits on the executive committee. Those moves sent a strong signal about the importance of AI, analytics, and data to the rest of the organization.

The chief AI and data officer introduced AI and analytics as an agenda item at C-level strategy meetings and convinced organizational leaders that the company’s data was a strategic asset. The executive gained a budget to fund strategic AI and data initiatives, influenced business units (BUs) to experiment with innovative AI models, and established data governance principles and processes in partnership with IT. The COE went on to create completely new value propositions, such as a digital pharmacy, well-being services, and chronic disease prediction and management, which aligned with the company’s strategic entry into well-being as a new, adjacent business in 2022.

A COE is also essential for companies seeking to address problems that are challenging and complex and have a potentially high value. Done well, the COE can eventually become a source of competitive advantage, as was the case at Securitas, a global security services company. After Securitas established an advanced analytics COE in 2018, the COE team chose to work on the tough problem of risk prediction. The team built on internal data (both free text and historical reports that yielded data on incident occurrence, timing, location, type of client) and external data (such as weather, demographics, and street maps). The AI model was then trained to predict the risk of an incident (burglary, vandalism, or even assault) and where and when it might occur, with 88% precision.

The prediction provided input to clients so they could better schedule guards and patrols, thus enabling them to tackle dynamic risk. For example, the model alerted a Swedish retailer with over 90 outlets as to which of its sites were the most exposed, the biggest risks at each site, and the factors driving those risks. This informed critical actions to significantly improve security for the retailer. Cracking the risk-prediction problem wouldn’t have been possible without a centralized approach that enabled Securitas to acquire the volume and variety of data needed and the more specialized AI experts required to staff a COE, according to then-CIO Martin Althén. Risk prediction delivered through an app soon became a competitive differentiator for Securitas.

A center of excellence is essential for companies seeking to address problems that are challenging and complex and have a potentially high value.

Focus on Standardization to Deliver at Scale

IOEs are almost by definition opportunistic and agile. Their key goals are speed and “good enough” solutions to the pressing needs of a BU or function. Consequently, IOEs are where proofs of concept are generated, bridging the adoption chasm between early adopters and the rest of an organization. But they also lead to inefficiencies due to the lack of standardized data and AI infrastructure, narrow data availability and capabilities, and the absence of mechanisms for sharing results and best practices.

Through the use of COEs, companies are able to shift the emphasis of AI applications from quick wins/proofs of concept to the rapid delivery of reliable business-focused AI solutions at scale. They do this by creating hardwired processes and standardized systems that can efficiently produce and deploy models. Additionally, the COE drives appropriate model governance to help the organization achieve a granular level of control and visibility into how AI models operate in production.

Standardized processes and a shared data and analytics architecture are crucial to bringing together all parties: users at the BU level who will benefit from the models’ insights/predictions, data engineers in IT, AI model developers, and the machine learning operations (MLOps) staff who will put the technology into production.

At a large U.S. grocery group, this began with formalizing the chain of command for implementing AI efforts: identifying who was the decision maker, who was responsible, who could intervene, and who would pay. The company decided that BUs would be the owners of the AI projects, after it emerged that they were far more successful at influencing IT to deliver needed improvements than AI and analytics leaders had been. The company then set standard expectations for response times and service levels for data scientists, MLOps, and IT related to building and productizing models and creating the data pipelines to put models into production.

Locate COEs Where They Best Serve Current Objectives

The structural placement of the COE within the organization depends on the maturity, decision-making processes, and corporate dynamics of the enterprise. The COE can remain as a stand-alone cost center that is either fully funded by the corporate headquarters or cofunded by all BUs. Alternatively, it can operate under IT as a separate unit with clear boundaries, or under a dominant BU or key function such as marketing.

For example, the COE at Securitas was set up as a stand-alone unit working with agile operating principles and open-source technologies — not the norm in the company’s legacy IT function. Later, it became part of the Securitas BU focused on digital security solutions. In contrast, Philip Morris International’s COE has stayed within the IT function to maintain easy access to data while avoiding the complexity of creating a new global unit; and financial services company Rabobank established a COE to accelerate the data and analytics transformation of the company’s international food and agribusiness unit.

These examples show that the COE is best placed under whichever role or division can facilitate execution — and thus capture value. Each of the alternatives offers varying degrees of autonomy, accountability, and collaborative potential. COEs that are truly autonomous can approach any part of the business with agency and empowerment to create value. The structure might also evolve to match the company’s strategic direction. We see this at Rímac. Although the advanced analytics COE started as a stand-alone entity reporting to the chief AI and data officer, after three years it was brought under the marketing function to enable a customer-oriented transformation around well-being services in the next strategy cycle.

Address the Incentives-KPIs Mismatch

Aligning incentives and sharing risk between the COE and the BU is fundamental to scaling AI. Since the COE does not operate in a vacuum, setting KPIs only for the COE gives it responsibility without power — and then it becomes even easier for skeptical BUs to claim that the COE is not generating value.

At Rímac, the COE’s objective was to increase gross profits by $15 million in a year. However, the BU with which this value was to be created did not have this objective on its scorecard, so it did not necessarily prioritize the resources, bandwidth, and effort needed to implement the AI models (or help to create them). Needless to say, the COE could not fully achieve these targets.

To rectify the situation, in 2022 the company moved to a shared-objectives scheme whereby the BUs had their corresponding share of value objectives and key results; this ensured appropriate effort and resource allocation. Also, proper accounting for the value-add was essential to establish a measurable KPI, thus enabling the correct ROI estimation for AI efforts. A senior executive there explained, “If the business head knows that his P&L or budget is being charged with US$500,000 a year to cover costs but the COE is generating US$5 million in operating revenue, it’s a no-brainer that the motivations on both sides will match.”

When the COE Is Not Enough

While COEs have been successful mechanisms used by many companies to gain more value from their AI capabilities, they can be insufficient for large, highly diversified companies with significant resources at their disposal. For those organizations, one of the drawbacks of the COE is that it lacks the domain knowledge about specific business areas. In one conglomerate we studied, the COE created a spend prediction and customer upgrade model for its hospitality business. The model provided insights to allow front-line employees to offer customers with certain profiles better rooms, spa packages, entertainment options, and other upgrades.

Although the model worked well from a technical point of view, the implementation failed because it simply could not be inserted into the staff’s existing decision-making and work processes. The COE head shared, “We knew we could do a lot of cool stuff; we also had the sponsorship of the hotel’s CEO, but we didn’t really understand the business. Our lack of knowledge didn’t allow us to ask good questions or incorporate the right features into the models. We then realized that in order to be successful, our data scientists needed to become specialists in domains like hospitality, mining, fisheries, etc., and not be generalists at the corporate level.”

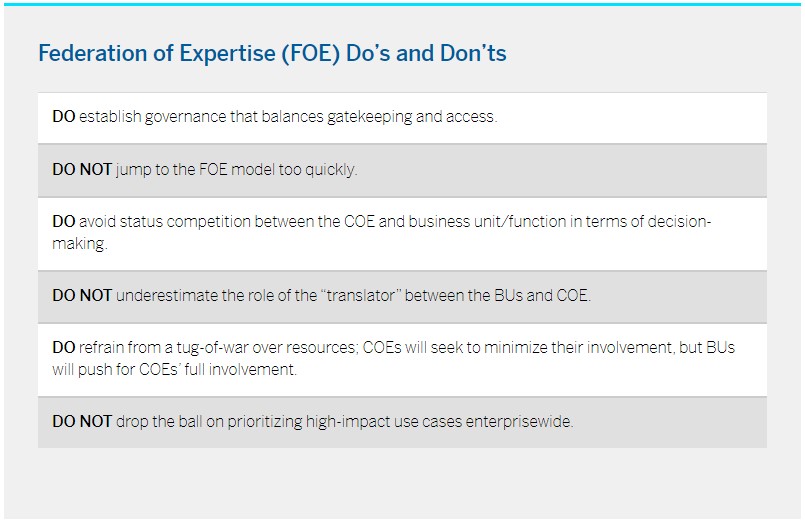

Second, with growing success and credibility, COEs tend to become a bottleneck. A telltale sign is when the COE goes from knocking on BU doors to find analytics projects to having a backlog of multiple BU projects vying for priority. As BUs end up queuing for access to stretched COE resources, a slowdown in scaling momentum ensues, which ultimately creates frustration on both sides. In these situations, companies may turn to a federation-of-expertise model.

The FOE model comprises two elements: a centralized base of knowledge, systems, processes, and tools; and decentralized embedded capabilities. Each BU pays for the embedded specialists (MLOps and development and operations personnel), and the team size depends on the profile and objectives of the business. The tech team focuses on building BU-specific analytical solutions and a catalog of algorithms and processes that can be used for data discovery, model monitoring, maintenance, retraining, and so on. Accountability is often achieved through a dual reporting line — to the BU head and to the CIO/functional leader — with joint business reviews to agree on the priorities.

At Procter & Gamble (P&G), the corporate center provides the central platform — for example, Microsoft Azure and a central data lake — and the BU builds the products on top of it. The embedded teams extract data from this system to create data hubs (which are further loaded with additional internal and external data sources) and build solutions that correspond to the needs of a specific BU.

The FOE structure enables the central team to have a bird’s-eye view so it can identify situations where a particular local solution could have multiple applications. The embedded team also has the autonomy to incubate bottom-up ideas that have the potential to be reapplied enterprise-wide. P&G deftly manages this balance between autonomy and control by leveraging a data science sandbox to create a BU-specific solution, testing it, and then replicating it in other units. For example, audience modeling, a highly valuable use case for digital marketing, does not need to be rebuilt unit by unit.

However, a danger with FOEs is that practices and tools can fragment across the company. When Rímac transitioned to a hub-and-spoke federated model, its health insurance BU proceeded to embed specialist capabilities by allocating a budget, pulling in some central experts, and recruiting new talent to speed up the process. Rímac avoided fragmentation by giving the COE head and three senior project leads responsibility for ongoing dialogue with the BU head and having them participate in management meetings to understand the business needs. It also trained the newly embedded talents on best practices and lessons learned from past mistakes and set guardrails to ensure consistency.

A key benefit of scaling up to the FOE model is that it drives a flywheel effect. Prioritization can be based on cumulative value: A project might not deliver significant benefits in the first round but could generate important data sets or tools that could be reused for multiple use cases in the future. As Harrie Schaap, Rabobank’s data and analytics transformation lead, explained, “It is no longer just about the monetary value or the ease of implementation. The bigger question is, by pursuing this use case, are we actually building a data position which will be a stepping stone to create substantial monetary value from the next use cases?” This effectively means advancing up the data science hierarchy, where executing one level unlocks greater potential at the next. As cost centers with shorter time horizons, COEs cannot assign priorities using the same logic.

More importantly, during tough times, the COE’s funding might be threatened, stalling progress. However, this issue is avoided in the FOE model, since federated AI projects don’t necessarily face the same cost-cutting pressures, so scale-up can continue.

COEs are generally cost centers, and BUs often push back on demands to fund a COE that they did not ask for in the first place. They may be skeptical about the new solutions proposed by the COE and doubt that they will generate sufficient value — at least initially. And they typically want to see ROI within the fiscal year, whereas some AI-related work might take multiple years to generate a positive return.

Transitioning from a COE to an FOE allows for a shift in the funding model — from a contribution-based system shouldered by the BUs to a dual funding model where the core team is funded by the corporate headquarters and each BU maintains its own data resources. This shift permits BUs to have greater control over both expenses and the ultimate outcomes.

Close the Feedback Loop

The strongest lever for scaling usage and adoption of artificial intelligence is to demonstrate that using AI tools has a positive financial impact on the business. It requires that the organization establish a feedback-loop flow from the BU to the MLOps team and, ultimately, to the data scientists. This helps ensure that the two most common problems in model building — applicability and model drift — are addressed.

Feedback from the business that, for example, an AI tool meant to improve lead generation is producing few conversions to customers enables the data analytics team to retrain the model with more labeled data and knowledge of the model predictions in the field. In fact, in some companies, central experts in the COE/FOE refuse to support BUs that don’t provide feedback on their models.

The strongest lever for scaling usage and adoption of artificial intelligence is to demonstrate that using AI tools has a positive financial impact on the business.

Continuous feedback also allows for faster flagging of model drift — when the AI tool’s own learning on the job changes its output in ways that make it less useful or even wrong. Mature companies carefully monitor performance measures such as model accuracy, error rates and types, drift in scores over time, and inferences from the model.

Process Change at Scale

The progression from solving particular problems to building new capabilities must ultimately result in work processes that are consistent across the organization. At Tetra Pak, a global leader in food processing and packaging solutions, the data science team identified a significant opportunity to optimize the safety stock for its base material (paper board) to minimize working capital while maintaining customer service levels. As the first step, it fine-tuned the stock forecasting formula using historical data on demand variability from customers and lead time variability from material suppliers. Successful pilots with the new formula enabled the team to build initial trust with the company’s supply chain planners.

The second step was more complex. The team looked at historical forecasts to identify the biases that influenced forecast errors. These biases stemmed from sales incentives to increase growth and supply chain incentives to reduce the cost to serve. With this insight, the team created a machine learning model that would provide a baseline replenishment forecast at the beginning of the planning process, which the planners could then enrich with additional insights such as demand signals. This required a series of significant process changes: redefining the forecasting process, reframing the roles and responsibilities of planners, and introducing new mechanisms to measure forecast accuracy and minimize the total cost to serve.

These efforts resulted in a 25 million euro ($27 million) reduction in working capital in the short term and a scale-up opportunity of an additional 43 million euros by applying the same machine learning forecasting model to other components, such as straws and caps. More importantly, both the data science and operations teams started thinking more holistically about how AI could be embedded to optimize inventory for specific customers with different service-level agreements based on forecast accuracy. Only when the processes are fundamentally changed can a data-driven approach become a strategic game changer.

Many enterprises are on a journey to gain broad value from data analytics and AI capabilities, but they are still far from the destination, often adrift among islands of experimentation. Instead, scaling AI requires two critical leaps that have less to do with the technology or resources and more to do with establishing appropriate organizational structures, operating processes, and metrics — and executing the changes with intentionality. While the past decade has been about experimenting with applying AI, the next decade will reward those organizations that really manage to scale it.