Skills Training Links Psychological Safety to Revenue Growth

Skills training for executives highlighting psychological safety and perspective-taking have been shown to improve business outcomes.

News

- Identity-based Attacks Account for 60% of Leading Cyber Threats, Report Finds

- CERN and Pure Storage Partner to Power Data Innovation in High-Energy Physics

- CyberArk Launches New Machine Identity Security Platform to Protect Cloud Workloads

- Why Cloud Security Is Breaking — And How Leaders Can Fix It

- IBM z17 Mainframe to Power AI Adoption at Scale

- Global GenAI Spending to Hit $644 Billion by 2025, Gartner Projects

Nick Lowndes/Ikon Images

Many organizations around the world recognize psychological safety (PS) as being crucial for innovation, collaboration, and transformation. Briefly put, psychological safety describes an environment in which candor is expected and won’t be penalized. Although it’s often covered in leadership training, most organizations struggle to convert a theoretical understanding of PS into bottom-line results. We’ve found that this gap can be closed through skills training in the context of real work.

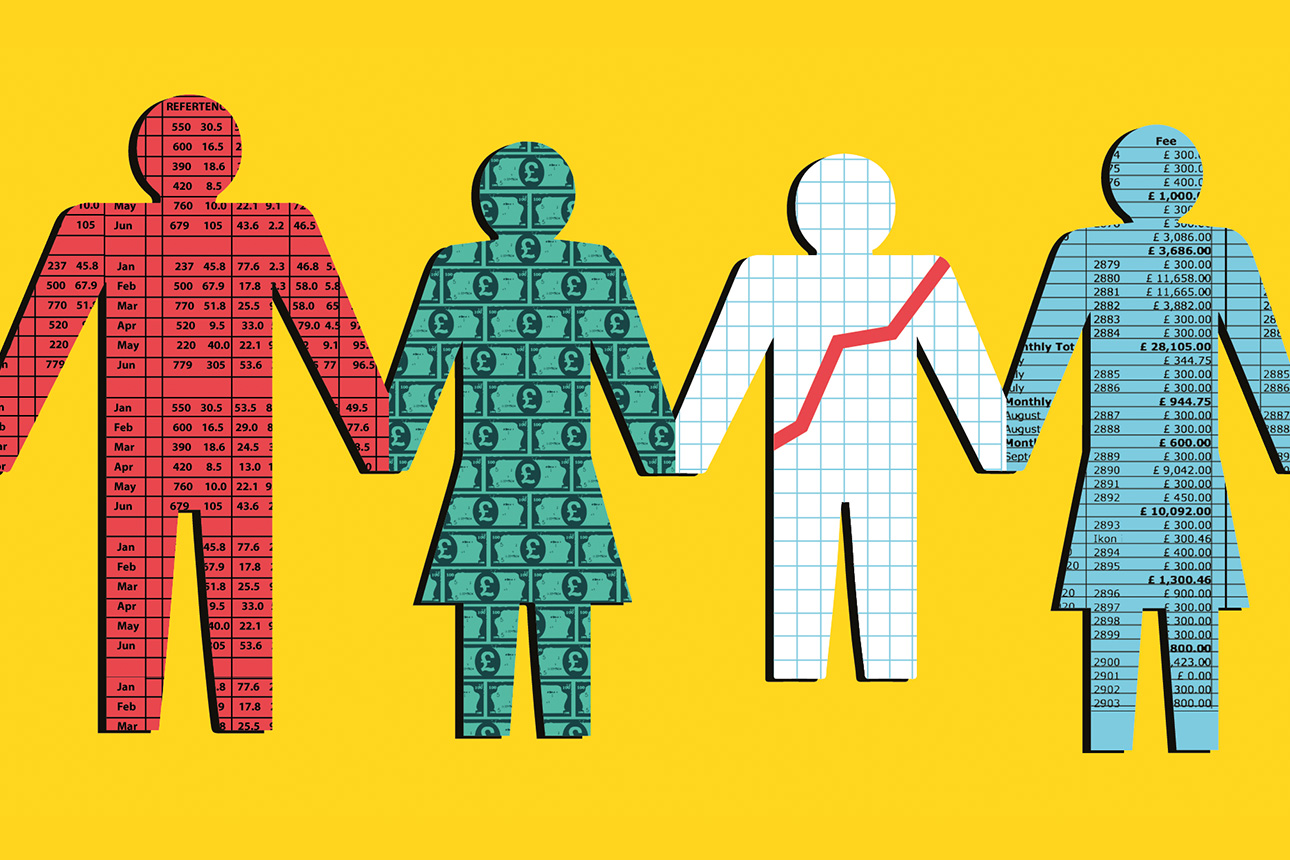

The investment bank at Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken (SEB), a 168-year-old Nordic financial firm, was able to realize the financial upside of improved PS by employing a management team intervention in which the concept was introduced to help the organization overcome transformation roadblocks. Members of the senior management team credit a specific two-hour training session as a turning point that enabled them to better pool their knowledge and expertise. As a result, they were able to achieve revenues 25% above yearly targets in a strategically important market segment.

Organizational performance can be improved by viewing psychological safety as a trainable skill that individuals develop with practice. Specifically, the ability to create an atmosphere in which people feel safe in taking interpersonal risks — by expressing unpopular opinions, disagreeing constructively, and sharing mistakes, failures, and other potentially embarrassing information — is an important skill in times of great change.

When Skills Training Leads to Revenue Growth: A Case Study

When SEB restructured its investment bank to better capture opportunities in the rapidly evolving financial industry landscape, the group’s newly appointed head of investment banking, Kristian Skovmand, launched a program called Collaborative Decision-Making and Strategic Progress. The program had already been used successfully by other senior leaders at SEB. This time, it involved the 10 leaders on the senior management team, including Skovmand, in a five-month team training initiative focused on two key areas:

- Training in PS skills to increase the level of candor, and in perspective-taking — that is, intentionally putting aside one’s own perspective to envision another’s viewpoint, motivations, and emotions.

- Applying and practicing these skills to make progress on specific complex challenges using structured dialogue techniques.

Importantly, the program combined skills training with hands-on work to solve real problems and make important decisions. The theory underlying this approach is simple: Demonstrate how interpersonal skills advance the business agenda while supporting participants in doing just that. Instead of offering the leaders immersive classroom experiences that would teach them ideas and practices that they could apply to real issues later, this approach supported them in working through important topics as a team. In particular, the use of structured dialogue enabled participants to use perspective-taking and other skills, with support, to solve pressing issues.

SEB’s co-head of equities, Johan Nyquist, noted, “Many problems were solved during the program, but the dialogue session, focused on our suboptimal collaboration around opportunities in equity capital markets, stands out as a clear turning point for us.” SEB’s 2022 annual report shows that the equity capital market (ECM) segment finished the year 25% over original revenue targets, materially contributing to the bank’s strong overall results and to the 5% bump in share price that followed the annual report’s release. Earlier that year, the investment bank had been struggling to meet those same targets despite record-breaking activity in the Nordic ECM market. “Important stakeholders, critical to success, did not communicate efficiently and coherently to improve SEB’s overall outcome,” according to SEB’s head of ECM. Another leader put it this way: “We all saw the opportunity from our own point of view, and we spent the majority of our time trying to convince the others.”

Halfway through the program, the four executives most engaged in ECM opportunities agreed that their usual approach to collaborating had prevented them from generating, and winning, new deals. They decided to schedule a dialogue session to address the problem. The structure of the session gave each participant several dedicated time slots to share their perspective on specific aspects of the target issue; meanwhile, the other participants were instructed to use perspective-taking skills to picture how the person sees, experiences, and feels about the issue and to write down the new thoughts and insights they had during the process. Switching between perspective-taking and advocating made it easier for participants to listen intently because they knew that they would have the floor later. The clear structure ensured that all participants spent a majority of the session listening, learning, and gaining a richer understanding of the issue at hand while ensuring effective turn taking — a predictor of team collective intelligence. Neuroscience research shows that engaging in dialogue that employs active perspective-taking also increases the generation of high-quality ideas.

One participant explained, “The intense structure helped us formulate what we felt was essential as a solution gradually took form.” Another said, “It is hard to know if it was the psychologically safe atmosphere that enabled us to share different perspectives and ideas or if the active perspective-taking created the psychologically safe atmosphere. Either way, the conversation was unlike any we’d had before, and the results that followed were obviously beyond what we had ever hoped for.”

We believe that psychological safety and perspective-taking work in tandem and that helping participants strengthen those skills and then apply structured dialogue to “real work” were key to the program’s success. The executives later agreed that the impressive 2022 ECM results wouldn’t have been achieved without the dialogue session and that the decisions that emerged created conditions that enabled SEB’s employees to collaborate effectively to reach record-breaking results.

“Psychological safety and perspective-taking were not new concepts to us; they had been the focus of highly engaging management conferences, as well as leadership programs,” Nyquist explained. “But before we got to practice the skills while solving real problems, our theoretical understanding of psychological safety had not led to significant changes in the way we worked together — especially in situations where we disagreed on strategically important topics like in the ECM example.”

How to Design Interpersonal Skills Training to Boost Performance

In a previous article, we highlighted active perspective-taking as an effective way to improve PS. Here, we’ll focus on how conducting skills training in the context of “real work” is a powerful approach to transformational change. Our experiences at SEB led us to develop four recommendations for leaders who want to make progress on strategic challenges and improve financial results by leveraging psychological safety and perspective-taking:

1. Focus on two levels in parallel: individuals and teams. Per, who designed and facilitated the program, credits his experience as a semiprofessional basketball player and coach with the insight that winning teams engage in training at two levels. Individual skills (such as shooting, passing, and dribbling) and team practice (complex gamelike drills where team members coordinate their skills to achieve shared outcomes) must be combined to produce optimal team performance.

On a related note, research shows that the intelligence of separate individuals on a team does not predict a team’s level of collective intelligence. Rather, interaction patterns and an ability to read each other is far more predictive of the quality of the solutions a team will create.

Of course individual skills matter. Clearly, a basketball team made up of players who can’t shoot, pass, or dribble is unlikely to win a championship, let alone a game, regardless of how many team drills they perform. This is why we propose that performance-focused team interventions, even those engaging top executives as at SEB, be designed to first ensure basic individual skills. Only then should they move into a blend of short skills-training sessions punctuated by longer sessions designed to practice the skills as a team, in a coordinated and structured way, and solve complex problems together.

2. Expand leadership responsibility. The team leader plays a large part in creating a psychologically safe environment. However, recognizing that PS is an individual skill and something that everyone — not just the leader — is responsible for can help a team reach the level of conversational skills and effective decision-making demonstrated by SEB’s investment bank.

By training working management teams on topics crucial to team success, all team members become more able to understand how they each influence the quality of conversations and decisions. They also become more able to hold each other accountable for perspective-taking and for the level of psychological safety in team conversations.

3. Keep strategy and performance front and center. Drastically improved decision-making and problem-solving capabilities come at a price. At SEB, that price was weekly skills-training sessions and bimonthly team offsites. This time investment was initially met with resistance by executives already working long hours and prioritizing critical tasks. Additionally, a few team members stated, with previous HR interventions as proof points, that prioritizing what they saw as soft skills over “actual work” was a waste of time. This is not unique to SEB but something we have encountered in many organizations.

To help skeptical team members understand that the program’s primary aim was to improve performance and make progress on strategy, the initiative was separated from the HR department. An advisory board for the Collaborative Decision-Making and Strategic Progress program was formed, consisting of SEB’s deputy CEO; and the heads of risk, large corporate and financial institutions, and SEB’s successful innovation studio. The advisory board met bimonthly to identify senior management teams that were about to launch ambitious strategies. Advisory board members then suggested five-month interventions to the leaders of selected teams.

When team members questioned the time investment, advisory board members could describe to them, based on their own experience, how the skills-training program had led to improved risk assessments, improved market share, expansion into new customer segments (as described in the Harvard Business School case study “Leading Culture Change at SEB”), and progress on strategic roadblocks, as in the ECM case — all of which created added revenues well over $100 million. (See the Harvard Business School case study “Leading Culture Change at SEB” for more details.) These short conversations shifted the focus from soft skills to executing the bank’s strategy and reaching financial targets, which in turn increased openness and reduced skepticism.

4. Link skills to short-term gains to counteract perceived costs. Even when you convince a management team to schedule an ambitious intervention like the five-month program at SEB, if the lag between the time investments and the returns (such as those measured by revenues) is significant, teams are unlikely to follow through.

By focusing an intervention on a real, current challenge, participants can see the impact and assess the future potential of this training. The goal is for them to leave the first session with firsthand experience of how their enhanced skills led to observable progress on issues they consider important. Thus, during the first offsite, teams practiced structured dialogue to make progress on a strategic hurdle they identified. The sense of progress experienced in the first dialogue session helped convince skeptics that the returns from using the skills and methods were greater than the costs. The ECM dialogue session is one of many examples in our data where teams and executives who had been skeptical of the time investment chose to schedule additional dialogue sessions beyond the original skills training program after realizing their link to improved results.

Skills-focused interventions involving senior leaders can be an effective way to get important work done by creating a climate of psychological safety that is enabled by perspective-taking in the context of a team’s actual work. This approach promises long-term benefits such as greater innovation, faster transformation, and improved inclusion, as well as short-term measurable performance gains — which are perhaps more important in terms of creating momentum for change. Such short-term gains can be pivotal to engaging skeptical senior leaders in the use, and promotion, of perspective-taking and psychological safety to solve tough business problems.