What Makes Successful Frameworks Rise Above the Rest

Business leaders can better assess and strengthen analytical frameworks using seven evaluation criteria.

Topics

News

- Gulf Nations Fast-Track AI Ambitions, UAE Leads Regional Readiness, says BCG Report

- AI Professionals form a Redefined Workforce. But Systemic Roadblocks Persist, Survey Finds

- AI-Driven Scams Surge as Microsoft Blocks $4 Billion in Fraud Attempts

- Identity-based Attacks Account for 60% of Leading Cyber Threats, Report Finds

- CERN and Pure Storage Partner to Power Data Innovation in High-Energy Physics

- CyberArk Launches New Machine Identity Security Platform to Protect Cloud Workloads

Frameworks are everywhere in business. Some, such as the BCG growth share matrix, Porter’s Five Forces, and SWOT analysis, have had a lasting impact on business strategy and practice. And many managers have created frameworks related to their own work. But why do some frameworks change the world while others … not so much? And how can business leaders best assess and strengthen the analytical frameworks they use?

What’s in a Framework?

Any kind of coherent thinking involves some form of conceptual framing. Conceptual frameworks are mental representations that order experience in ways that enable us to comprehend it. While philosophers and cognitive scientists devote a good deal of thought to these constructs, few of us ponder the matter much, no matter how often we use a particular framework.

Take the ubiquitous income (P&L) statement as an example: It’s a simple yet powerful way to make sense of the myriad transactions that occur in a business. Once we have framed financial exchanges as either revenues or expenses, we can begin asking and analyzing important questions about the business (such as “Why are we losing money?”). By adding a further dimension of assets and liabilities — using a balance sheet framework — we can derive a huge range of ratios and relationships that provide further insight for managing and valuing the enterprise. These concepts — revenue, expense, asset, liability — are so familiar that we may not even recognize them as conceptual structures. Yet there is nothing inherent in this balance system, and it is possible to imagine alternative accounting systems.

While all frameworks are essentially arbitrary ways of sorting data, some are so powerful and pervasive that they shape how we see the world. What sets the best ones apart? Below is a rubric of seven criteria for evaluating business frameworks.

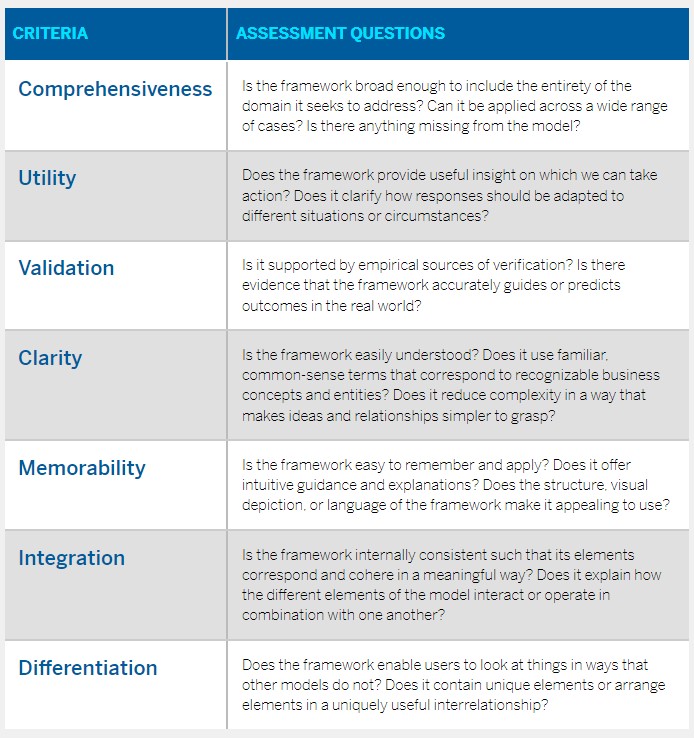

Evaluation Rubric for Analytical Frameworks

These seven criteria delineate the specifics of evaluating business frameworks.

Comprehensiveness

To be effective, a framework must cover a broad spectrum of the domain it seeks to explain. Such frameworks are either empirically comprehensive (encompassing a wide array of elements that observation and experience have shown to be important) or logically comprehensive (structured in a way that makes them complete by definition).

Take the example of McKinsey’s empirically comprehensive 7S model of organizational effectiveness, which has proved to be an enduring management construct. The model was developed in the late 1970s to describe how multiple organizational “levers” need to be aligned to enable high performance.4 At the time, most organizational strategy focused on a single s, structure — the formal hierarchical and reporting relationships in a company’s org chart. By expanding the analysis to include other elements of organizational context — strategy, systems, skills, style, staff, and shared values — the 7S model represents a more complete and useful account of internal factors affecting performance. There is not, however, an a priori reason there should be exactly seven elements of the model (rather than, say, five or 12), let alone a reason they should all start with the letter s. It’s possible that there may be something missing from this model.

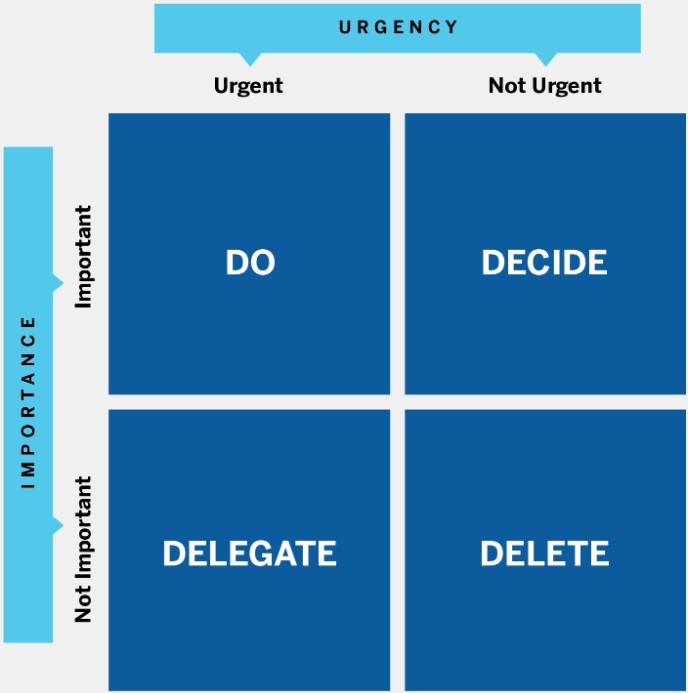

In contrast, the Eisenhower matrix of time management is logically comprehensive. In this framework, purportedly developed by former President Dwight D. Eisenhower and popularized by Stephen Covey, all possible tasks can be arranged into one of four boxes created by the intersection of two axes: the importance of the task and the urgency of the task.

The Eisenhower Matrix of Time and Task Management

This simple matrix, attributed to President Eisenhower, is logically comprehensive (and ubiquitous in business contexts).

Consultants famously love 2×2 matrices, used to represent everything from product portfolios to situational leadership strategies. The reason for their popularity can be summed up by the acronym MECE: mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive. A framework is MECE if it is composed of distinct, non-overlapping categories (mutually exclusive) and if these categories together cover all possible elements (collectively exhaustive). Because well-constructed 2×2 matrices are always MECE, they are logically comprehensive. (Credit for the concept of MECE goes to Barbara Minto, McKinsey’s first female MBA hire in 1963 and an influential figure in the history of management consulting and the development of analytical frameworks.)

While comprehensiveness is important, it’s not enough on its own. At worst, comprehensive frameworks are merely tautological. Consider a model that proposes that there are two kinds of people: those who believe that there are two kinds of people, and those who don’t. True, but not helpful. We need additional criteria for evaluating the quality of analytical frameworks.

Utility and Validation

Perhaps the most clear-cut criterion is that of utility: Does the framework tell us something useful or interesting about something important? The growth share matrix, created by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) founder Bruce Henderson in 1970, is perhaps the most renowned analytical framework in business. Built on the insight that market leadership promotes sustainable advantage, the matrix offered a way to answer a pressing question for then-dominant conglomerates and diversified industrial companies: how to invest resources across their product portfolios. The genius of the tool was that it provided a simple categorization of the product portfolio in a way that enabled managers to take action.

A second dimension of utility might be called adaptability — whether a model can be tailored to apply in different circumstances with different facts. Again, the BCG growth share matrix (or BCG matrix) showed its utility in this regard. A growing army of BCG consultants fanned out across the globe to implement the matrix in different industries. At its height, the framework was used by nearly half of all Fortune 500 companies and propelled BCG to prominence.

The next criterion, validation, is related to but separate from utility: Is the validity of the framework supported by empirical evidence and observable data? Insights about the sustainable cost advantages conferred by market leadership, upon which the BCG matrix framework is based, emerged from BCG’s rigorous empirical research of the experience curve effect. Another recognized framework, McKinsey’s granularity of growth, disaggregates revenue growth into three components (market momentum, M&A, and changes in market share) to identify pockets of growth opportunity. The best frameworks produce reliable insights that are grounded in observable data. The McKinsey framework is powered by a database of hundreds of companies across a range of industries and subsegments.

The economist and Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson famously asserted that the theory of comparative advantage was one of the few propositions in the social sciences that was neither false nor trivial. That’s the sweet spot for the criteria of validation and utility: non-false and nontrivial.

Clarity, Memorability, and Integration

The next three criteria are linked to what can be called the “elegance” of a framework, but they affect more than just aesthetics. These important factors contribute to the usability and distinctiveness of a model.

Clarity covers a number of related ideas, such as familiarity, simplicity, and parsimony. Frameworks that use common-sense language in a familiar way are easier to understand and use. The ability of a model to simplify facts and relationships in a way that brings them closer to intuition can cut through complexity to facilitate analysis. Parsimony refers to the idea that frameworks should be economical in limiting the number of explanatory factors to the absolute minimum. Multilevel models with dozens of categories, drivers, and subdrivers may achieve comprehensiveness at the expense of comprehensibility. Framework makers should strive to follow the dictum attributed to Albert Einstein: Things should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.

Structure, visual depiction, or language can help make a framework memorable. The BCG matrix’s use of symbols and animals (star, cow, dog, and question mark) makes it instantly recognizable and helps people remember the categories. Likewise, the decision to use seven sibilant terms for the 7S model surely played a role in its enduring success. And anyone who has ever taken a marketing course will probably recall that there are four P’s and five C’s to consider in any business plan. In the crowded market of ideas, attention-grabbing words and pictures can aid recall and make ideas sticky.

Integration evaluates the consistency and coherence of the model and the extent to which it hangs together logically. Models that offer many explanatory factors may suffer from weak integration if how the various elements work together or the relative impact of each is unclear. For example, can strengths in some areas compensate for deficiencies elsewhere? Does the framework offer a perspective on which factors to prioritize or how to sequence efforts to optimize particular elements? Frameworks can also fail to be integrated if supporting ideas and structures are poorly ordered or inconsistent with the overarching thesis.

Differentiation

A framework can be differentiated from others either by recombining familiar elements in a distinctive manner or by proposing novel elements that enable users to see things and take action in a new way.

When Michael Porter proposed in 1980 that there were a small number of “generic strategies” that companies could adopt in pursuit of competitive advantage, this was news. Strategy in the 1970s had been dominated by the pursuit of market share and scale in accordance with the logic of the experience curve. Porter’s argument that companies needed to choose among the cost leadership, differentiation, and focus strategies — with the aid of many new analytical frameworks — made his approach highly distinctive.

Twenty-five years later, proponents of the blue ocean strategy sought to upend Porter’s competitive strategy, claiming that companies could break the trade-off between cost and differentiation and render competition irrelevant by innovating entirely new market spaces. This novel take on strategy again required new analytical tools, such as the strategy canvas and the four actions framework. While frameworks need not break entirely new theoretical ground, they should offer a fruitful insight or a valuable perspective that others do not.

Like the main character in Molière’s play The Bourgeois Gentleman, who is surprised to discover that he has been speaking prose all his life, we may not always realize when we are using conceptual frameworks. Still, we recognize them as essential management tools. Using the seven criteria discussed here can help anyone create more effective frameworks for their business.